China is using its huge digital surveillance system, and the threat of sending family members to reeducation camps, to pressure minorities to spy on their fellow exiles.

Yet even as he sat thousands of miles away in a quiet town in Sweden, he knew the police in his home country held something over him that could compel him to do just that — the freedom of his teenage son.

“What could I do?” O. said. “I told them, ‘My son is in your hands. He is the only thing that matters to me. I will do whatever you ask.’”

O. and his son belong to an ethnic group called the Uighurs, a Muslim minority group who make up close to half the population of Xinjiang (East Turkistan), a sprawling region in China’s west. There, China’s government has built one of the world’s most sophisticated surveillance states. Measures used there include techniques like DNA collection, iris scans, and cellphone surveillance, and they are disproportionately targeted at minority groups. Hundreds of thousands of Uighurs have been sent to internment camps that are shrouded in secrecy over the past two years. None have been formally charged with a crime.

But if you’re Uighur, escaping China doesn’t mean you’ve escaped the surveillance state.

BuzzFeed News interviewed 10 people in the exiled Uighur community who were targeted by Chinese state security after they moved overseas. They come from all walks of life — from waitstaff and fruit sellers to businessmen and government officials. BuzzFeed News is not naming the majority of these people to avoid endangering their family members who still live in China, because the government regularly punishes Uighurs’ families for real or perceived transgressions committed while abroad. Their accounts, as well as dozens of WeChat and WhatsApp messages and voice recordings that they provided to BuzzFeed News, shed light on the methods and processes the rank and file of China’s security apparatus use in surveilling Uighur exiles and fomenting deep-seated mistrust within their communities.

That China spies on and pressures its exiles — particularly ethnic minorities and those involved in activities deemed political — is not new. China has used such tactics since at least the 1990s to put pressure on those it believes are seeking to undermine the state. But Uighur exiles, Western academics, and advocacy groups say this pressure campaign has gotten far more aggressive over the past two years and has been bolstered by digital surveillance tactics.

China has ramped up repression of Uighurs because of fears of separatism and extremism in Xinjiang (East Turkistan), and Uighur militants were responsible for a series of knife and bomb attacks in public places in 2014 and have fought alongside extremists in Iraq and Syria. But rights groups say the government’s crackdown amounts to the collective punishment of millions of people over the actions of a handful.

Every person interviewed for this article said state security operatives told them their families could be sent to, or would remain in, internment camps for “reeducation” if they did not comply with their demands. It was a campaign, they said, that aimed not only to gather details about Uighurs’ activities abroad, but also to sow discord within exile communities in the West and intimidate people in hopes of preventing them from speaking out against the Chinese state.

“China’s now got the capacity and willingness to reach out across sovereign borders to influence the behavior of others,” said James Leibold, an associate professor at La Trobe University in Australia. “With Chinese citizens of Chinese heritage, they may want to win them over, but with Uighurs they want to squash them. Their willingness to do this is not only in a covert way, but now increasingly in an overt way.”

O.’s story, which is corroborated by WeChat messages and voice recordings of his conversations with his mysterious handler, is a common one. (BuzzFeed News also spoke to a close friend O. had confided in as the events were taking place, though O.’s handler could not be reached to independently verify his identity.) O. and his son left Xinjiang (East Turkistan) in 2014, when it was much easier for Uighurs to leave the country. They moved to Turkey, where O. believed his son could get a better high school education and perhaps win a scholarship to a good university.

Lots of teenagers would resent their parents for uprooting them, but O.’s son, then 15, loved Istanbul. He dove into books on Turkish culture and discovered he had an instinctive knack for languages, from Japanese to English. In his spare time, he loved to sketch, filling notebooks with drawings of cartoon wolves and superheroes.

The two moved into a neighborhood in Istanbul where many Uighur immigrants lived, and O. found a job waiting tables at a restaurant, trying to save up money. In January 2016, O.’s son said he wanted to take a trip back to Xinjiang (East Turkistan) to visit his mother and grandmother. O. didn’t see any problem with it and gave his son permission to travel.

But immediately after O.’s son landed in Xinjiang (East Turkistan), he disappeared. O. panicked and called relatives back home. Eventually he discovered his son had been detained by police.

O.’s son was released two months later, but he never made it back to Turkey. His passport was seized by authorities who suspected him of traveling to Syria to join extremist groups. (O. says he did no such thing.) O. left Turkey during this time too; he went to Sweden to seek asylum, believing he could now never return to China.

Kevin Frayer / Getty Images

A mix of ethnic Uighur and Han shopkeepers hold large wooden sticks as they are trained in security measures on June 27, 2017, next to the old town of Kashgar, in the far western Xinjiang (East Turkistan) region, China.

Uighurs are regularly sent to reeducation camps when they are found to have had contact with family or friends who are outside China. Because of electronic surveillance and the fact that police physically check Uighurs’ text messages and calls at checkpoints all over Xinjiang (East Turkistan), it is nearly impossible to hide these interactions. For this reason, O.’s family told him to stop trying to contact his son.

So O. settled for obsessively scrolling through and refreshing his son’s WeChat Moments — a component of the chat app that’s similar to Facebook News Feed, full of candid pictures and life updates. The cheerful superhero drawings his son used to post had vanished. In their place were dark sketches of hideous monsters and ghouls that terrified O. He worried about the toll detention might have taken on his son’s mind. Then this March, O.’s son disappeared again, this time to a reeducation camp.

Three days later, O. started getting WeChat messages from a state security operative, who said he was from O.’s hometown and had registered a Xinjiang (East Turkistan)-based account. He told O. his real name, and O. believed he was who he said he was because of the detailed information he had on O.’s family, and because of the fact that he could freely contact O. even though he was abroad.

The state security operative, who is a Uighur himself, told O. he had to provide information about the Uighur community in Turkey, including phone numbers, names, and information about their activities. O. asked him whether his son was safe.

“All the kids who have been abroad must attend a patriotic education course,” the operative told O., according to a recording of the conversation, which took place this April.

“I don’t get it… Is he still locked up?” O. asked.

“No, no, it’s a kind of school,” the operative responded. “A political education school. Education is important for kids, you know.”

The operative told O. that he would be happy to keep sending him news of his family — he might even send him a photo or two. O. needed him for this, he said. “When everything is done, if everything is going as well as we expect, then I can try to apply for a permit for you to call each other. Maybe once a month.”

“I’m happy to hear that,” O. said.

Google Earth

A satellite photo of a Chinese reeducation camp near Korla city in central Xinjiang (East Turkistan). GPS coordinates were provided by a Uighur exile who had visited the camp.

Reeducation camps of the kind O.’s son was sent to have been opening by the dozen all over Xinjiang (East Turkistan), but although those inside are taught Chinese language and Communist Party propaganda, they are more like secret internment camps than places of learning. Surrounded by high walls and loops of barbed wire, the camps sometimes house hundreds of Uighurs and other ethnic minorities.

Those inside have reported dire conditions, including food deprivation, extended solitary confinement, and other serious abuses. Because reeducation in China is not considered criminal punishment, there is rarely any documentation given to families. People often disappear, sometimes in the middle of the night, and their families later discover they have been taken to the camps.

Threatening the family members of exiles with punishment in China has been a longstanding tactic of the country’s security authorities, and it’s reportedly been used against high-profile dissidents including Anastasia Lin, the Chinese-Canadian beauty queen and religious freedom advocate, and ethnic Uighur reporters for Radio Free Asia.

But as the reeducation camps sweep up hundreds of thousands of Uighurs based on criteria not divulged outside the government’s own systems, it’s become far easier for the state security apparatus to threaten exiles like O. over their families’ freedom and safety.

“The [Chinese] police seem to increasingly have the ability to maintain complete information on all Uighurs living overseas,” said Omer Kanat, director of the Washington-based Uyghur Human Rights Project. “It has mostly gotten worse through more use of imprisonment of them or their families as a threat, if Uighurs do not agree to spy on their fellows.”

China’s Ministry of Public Security did not respond to a request for comment, and the Foreign Ministry has not acknowledged that the camps exist. But glowing state media reports have bragged about reeducation camps as free facilities that enable Uighurs to self-improve and see the error of “backward” religious practices like excessive prayer or wearing religious garb. But the fact that state security operatives use the prospect of these camps as a threat to Uighurs contradicts this notion, suggesting they know that it is, in fact, a punishment.

Those interviewed for this story said that surveillance of exiles starts before they even leave, when they’re applying for passports.

Before 2015, the government had temporarily loosened restrictions on Uighurs getting passports, and many people subsequently left the country — migrating abroad, studying at foreign schools, or traveling. Then in late 2015, it seems the restrictions tightened again. Though rules appear to differ district-to-district, many Uighurs described having to get sign-offs from many government offices — sometimes paying thousands of yuan in bribes — to obtain passports.

K., a former accountant from the city of Kashgar in Xinjiang (East Turkistan)’s southwest who comes from a wealthy family, said he paid as much as $10,000 in bribes to obtain a passport in 2015 — a measure he took after police made it clear he was likely to be taken away to a reeducation camp. His two older brothers had already disappeared.

Before state security authorities would agree to sign the paperwork to issue K. a passport, he said, he had to record a voice sample, allow police to take a 360-degree portrait of him and film him as he walked to record his gait. He also had to provide a single eyelash. The police never told him what these records were for.

K. realized after leaving the country that the voice and video recordings were likely for facial and voice recognition, and the eyelash was for his DNA.

Several people said one requirement for Uighurs going abroad was to provide contact information for every living family member as well as contacts abroad and a letter from their employer stating the person would not misbehave while overseas.

“The power of the state security authorities is massive,” K. said. “If they take someone away and they turn up dead, you cannot so much as ask what happened. There is no other government agency that has oversight over them. They are as powerful as an emperor.”

K. now lives in a city in the US. He said state security operatives began contacting him after he landed. But he had little information to provide them, so they left him alone.

Ozan Kose / AFP / Getty Images

A woman holding the flag of East Turkestan — a name used for Xinjiang (East Turkistan) by Uighur separatists — spits on a poster of Chinese President Xi Jinping during a protest in front of the Chinese consulate in Istanbul, on July 5.

O. started cooperating with the state security operative, who later sent him proof of his identity. O. sent the officer the names of two Uighurs he knew in Turkey, knowing neither was involved in political activities, and that they both held pro-government attitudes anyway.

As soon as he tapped “send,” he was wracked with guilt.

“I can’t believe this is my situation now,” he said. “I’m a spy for the Chinese government.”

O. knew exactly how brutal the system could be. In his early twenties, he worked as a police officer in his home city. Back then he was idealistic. Like everywhere in China, people in Xinjiang (East Turkistan) were getting richer, and he hoped the government would bring more prosperity to the region if police could enforce stability.

But years on the police force made him feel disillusioned. There are many Uighur police officers in Xinjiang (East Turkistan). But not being part of the majority Han Chinese ethnic group meant it was very difficult to be promoted past a certain level.

“You can be vice this or vice that, but never in a real position of power,” he said. And being on the force, he started to see corrupt officers fabricating evidence or attacking Uighurs without cause.

“That’s why I feel guilty,” he said. “I know this isn’t right. I know that there is no such thing as the law there.”

Kanat of the Uyghur Human Rights Project said exiles are under more scrutiny in urban centers where there are large populations of Uighur exiles, especially Washington, DC, where he lives.

“Some Uighurs choose not to live in the DC area to try to avoid the notice of the authorities. Some Uighurs in the diaspora avoid even visiting the DC area,” he said. “The Chinese police ask Uighurs if they have ever traveled to Washington, DC, and they receive more questioning if they answer yes.”

Tahir Imin, a Uighur academic who lives in the DC area, left behind his wife and their young daughter when he moved to Israel for graduate school. Even though he said more than a dozen of his family members have been sent to reeducation camps, including his brother and sister, he insisted that his real name be published in this article because he believes it will bring more attention to what’s happening in Xinjiang (East Turkistan).

More than anything else in the world, Tahir loves his daughter, now 7 years old. In the photos he keeps on his cellphone of them together, her black hair is cut in a pixie style. In one picture, she’s carrying a pink umbrella, a smile creeping across her heart-shaped face as Tahir hoists her onto his shoulder.

Courtesy Tahir Imin

Left: Tahir Imin and his daughter; right: a WeChat conservation Imin had with a state security agent.

Tahir was first contacted by Chinese state security officers last year, while he was in graduate school in Israel. At first, he was trying to keep a low profile there, but campus police inadvertently exposed him when they contacted the Chinese Embassy on his behalf after his house was robbed. A state security officer got in touch, urging him to cooperate with their demands. “You should think about your family,” the operative said.

Tahir believed he’d be sent to a reeducation camp immediately if he returned home. So he applied for a visa to the US and fled there last year, hoping he would be better protected. Once he got to DC, though, the same operative continued to harass him, telling him he could not escape no matter where he lived, and that the Chinese government had informers everywhere.

Tahir kept trying to call his family, but his wife told him he was causing them trouble. She asked him for a divorce, he says, in hopes that Chinese police would stop asking her about him. Then in February this year, out of nowhere, his daughter called him.

“She told me, ‘Father, you’ve brought a lot of troubles to my mother and me, and you are a bad person. The police are the good people and they are helping us. You shouldn’t talk to us,’” he said. There was no question in his mind that she had been asked to say the words.

After that, his family deleted his contact on WeChat, and he hasn’t heard from them since April. He has heard through the grapevine that much of his extended family has been sent to reeducation camps — but he believes his ex-wife and daughter are still free.

Amid all this, a state security operative continued to ask him to send information about others in the Uighur community. Finally, in June, he lost his temper.

“Before last week, I was also very afraid of them,” Tahir told BuzzFeed News a week after that conversation. But something inside him had snapped.

“I said, ‘Why would I cooperate with you? I know how brutal the Chinese police are. I don’t want to listen to you ever again,’” he recounted.

The operative, who is himself a Uighur, reminded him that his daughter was in their hands in a voice message that Tahir shared with BuzzFeed News.

“Your daughter won’t turn out to be a traitor like you when she grows up,” the operative said. “Your daughter will study hard and become useful to her homeland, to the nation, and to the Communist Party.”

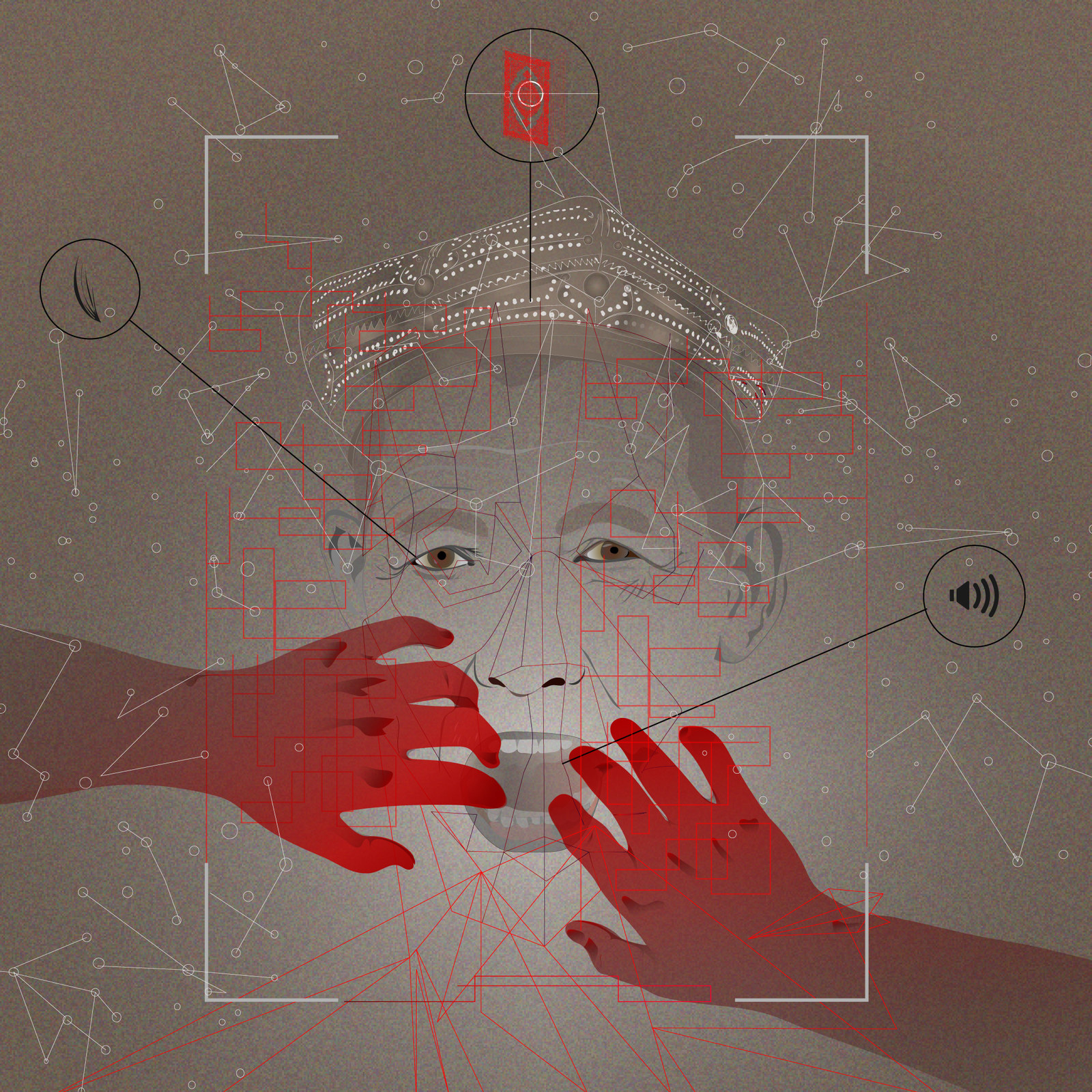

Efi Chalikopoulou for BuzzFeed News

State security operatives approaching Uighurs abroad for information on their communities has become so common that it has sowed a deep mistrust in these overseas communities and a pervasive feeling of being watched, those interviewed for this article said.

“There’s a high-level sense of fear and paranoia among the exile communities,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “There’s a lot of distrust among each other … It’s much more than the Han community abroad.”

The lack of trust has impeded efforts toward activism abroad, even as many Uighur groups are seeking to pressure Western governments to push back on China’s use of mass surveillance and reeducation camps through large political demonstrations.

“The catalyst for the mistrust is China’s deploying a wide network of spies amongst the Uighur community,” said one exile in Sydney. “This mistrust plays out as a hurdle to cooperation between different individuals and groups in political activism.”

Uighurs often don’t show up at protests because they’re afraid of being photographed or informed on, he said.

It’s clear that the sense of being watched, even when abroad, has had a chilling effect on Uighur communities everywhere from Sydney to Washington. S., a Uighur businessman who lives in Istanbul, received an unsettling photo from a Chinese state security operative. It showed S. attending a funeral for a prominent person in the Uighur community in Turkey. S. couldn’t figure out if the operative had gotten the photo from someone else in Istanbul or through electronic surveillance. But since then, he said, he has avoided being seen in public at gatherings where there are many other Uighurs present.

The majority of Uighurs in exile cannot communicate with their families back home for fear of endangering them. In this regard, S. is lucky. In a community where people speak as if all their digital communications are monitored, he found a low-tech workaround by way of his sister’s business partner, a Turkish man who lives in Xinjiang (East Turkistan) but sometimes travels home to Istanbul.

During these visits, the Turkish man would sometimes stop by S.’s apartment in a working-class neighborhood of the city. He would show S. messages and pictures from S.’s sister, and bring news of who in the family was still free and who had been taken to the internment camps. The man will not give S. his contact information because he fears his cellphone is being surveilled, and they’ve never communicated using an electronic device. All S. can do, as he thinks of his family, is wait and pray that the man will show up at his door again.

On one of these house calls, the Turkish man told S. that Chinese police had shown his parents a photo of S. in Turkey wearing a long beard — a practice that’s banned by the government for Uighurs in Xinjiang (East Turkistan). Since then, S. started wearing his beard shorter.

“I worry about spies all the time, even today,” S. said at a restaurant in Istanbul. “If I hadn’t heard from others that you are trustworthy, I would not be here.”

BuzzFeed News

A woman drives along the walls of a reeducation camp decorated with a propaganda poster in Kashgar, October 2017.

The issue of Chinese spying on exile communities is well-known in the West. A Swedish courtconvicted a man of spying on the Uighur exile community in the country on behalf of the Chinese government in 2010, and a 2011 case in Munich charged three men with spying on the Uighur community in that city. A review of public documents related to asylum claims in Australia shows that the threat of Chinese espionage activities in exile communities has been repeatedly used as evidence for Uighur refugees to be granted asylum.

But for Uighurs who receive these requests from Chinese state security, it seems authorities outside China are of little help.

“You understand the position I’m in,” said O., who is still waiting to learn whether his request for asylum has been granted. “I’m doing something illegal in Sweden, but if I stop, they will take my son.”

O. said he repeatedly approached Swedish authorities, including the police and even the Swedish Security Service, the country’s domestic security agency, with a written report of what had happened to him, which he also provided to BuzzFeed News. He has not yet heard anything back.

Dag Enander, a spokesperson for the Swedish Security Service declined to comment on specific cases or answer questions about the organization’s operations, but said, “we see unlawful intelligence activities targeting refugees as a very serious crime.”

“The Swedish Security Service makes every effort to prevent and counter any unlawful intelligence activities carried out in Sweden against refugees,” Enander added. “Such unlawful activities are often extensive, branched out in several countries, and take a considerable amount of time to investigate. The Swedish Security Service follow up and investigate any indications we receive that unlawful intelligence activities targeting refugees may be taking place in Sweden.”

After O. cooperated with the state security operative for months, his son was released from the reeducation camp. It had been so long since he had spoken to his son that he almost seemed like a stranger.

“Your son has grown a lot. Your wife said she needs to buy new clothes for him,” the state security operative told O., according to a recording in mid-May. “They are at the train station by now.”

O. asked if he could phone his son, who he hadn’t seen since he got on that plane leaving Istanbul in 2016.

“It’s not good to call him for the time being,” the operative said. “There is a strict control on it, you know. It can get them in trouble. Let’s wait a bit.”

“We can help each other,” he added. “I can help you here, and you can help me there, as we discussed last time — right?” ●

Megha Rajagopalan is the Asia correspondent at BuzzFeed News.

Contact Megha Rajagopalan at megha.rajagopalan@buzzfeed.com.