A new report from the Uyghur Human Rights Project details the Chinese government’s severe restrictions placed on Uyghur Internet users.

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online documents how Chinese authorities have exerted effective control over how Uyghurs seek, receive and impart information online in East Turkestan by employing technical and legislative strategies, as well as the use of the criminal justice system to create an atmosphere of fear, intimidation and self-censorship. UHRP interviewed a number of Uyghurs versed in the Internet culture of East Turkestan, experts on Chinese Internet censorship, as well as regular Uyghur users of the Internet in compiling the report.

“It is no surprise Chinese officials have placed unprecedented controls over the Uyghur Internet. They fear that an open online environment in East Turkestan will expose egregious human rights abuses committed against the Uyghur people under their administration,” said UHRP director, Alim Seytoff. “This report is the most comprehensive analysis available on the systemic repression of Uyghur online activity. The Chinese authorities can, at will, imprison Uyghurs who peacefully express dissent online and deny Uyghurs access to the Internet at the flick of a switch.”

“The Internet in East Turkestan is not the vehicle for empowerment, accountability and freedom that it is in the democracies of the world. What it represents, however, is another means for the Chinese state to disseminate propaganda and falsehoods about the Uyghur condition, as well as to flush out its perceived enemies,” added Mr. Seytoff.

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online finds that the Uyghur community in East Turkestan face directed censorship, denial of access and targeted detentions. The measures enacted by Chinese officials have resulted in an Internet space among Uyghurs that is not only tiny in comparison to its population, but also demonstrates the violation of the fundamental right to freedom of speech and association.

In East Turkestan, the Chinese state particularly employs the measure of Internet shutdowns, as illustrated in the unparalleled 10-month blackout in the post-July 5, 2009 period. While shutdowns result in government control over information dissemination in East Turkestan, they have also led to the deletion of vast amounts of data on Uyghur websites. UHRP records that the 2009 Internet shutdown and subsequent “restoration” of service was a devastating loss of information across a broad spectrum of subjects concerning Uyghurs, as an estimate of over 80% of Uyghur websites did not return after Internet service was restored.

Censorship and blocking of content posted online is also of great concern. Although, censorship and blocking of content is prevalent across China, moderators of the popular Chinese social media site Sina Weibo deleted 50% of social media posts in East Turkestan as opposed to 10% of posts in Beijing.

China has also employed legal instruments to ensure the Internet in East Turkestan remains an antithesis to the open forum experienced in democratic nations. In addition to a national legislative framework to deny Chinese citizens the ability to freely seek, receive and impart information online, regional and local authorities in East Turkestan deny residents, especially Uyghurs, the right to freedom of speech and association.

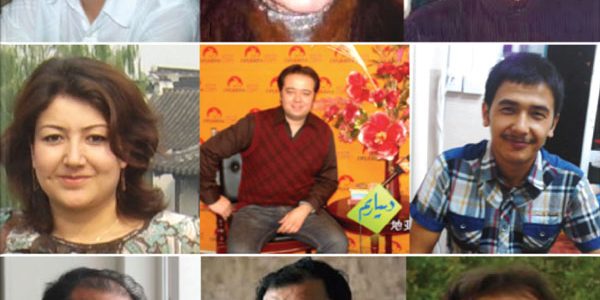

Chinese officials have leveraged this extensive regulation of the Internet to enact arrests, convictions and harsh sentencing of Uyghur Internet users. The detention of webmasters and bloggers, especially from the Uyghurbiz, Diyarim, Salkin and Xabnam websites is an illustration of Chinese officials implementing this hardline. For example, Salkin contributor, Gulmire Imin, received a life sentence in 2010 for “splittism, leaking state secrets and organizing an illegal demonstration.” In an opinion on Gulmire Imin’s case, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found China to be in contravention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Ms. Imin’s detention to be arbitrary.

UHRP urges the Chinese government to meet its international obligations and observe its own laws regarding freedom of speech and association. UHRP also encourages the Chinese government to view the Internet as a platform for open debate and reconciliation. Furthermore, UHRP asks the international community to publicly express concern over the severe limitations placed on Uyghur online freedom and urge China to review and reform its body of regulations governing the Internet in order to meet international human rights standards.