Islamic domes and signs in Arabic are being pulled down and no new ‘Arab style’ mosques can be built under campaign that has Hui communities worried

Every Friday, the Nanguan Grand Mosque springs to life as local Hui Muslims from Yinchuan, capital of their official heartland, gather for the most important prayer of the week.

Just after midday, men in white prayer caps file into the mosque and disappear behind a gate adorned with gold Islamic motifs and three green domes, each topped with a silver crescent moon that gleams in the sun. It was one of the country’s first Middle Eastern-style mosques, built in 1981 to replace a Chinese one that fell victim to the Cultural Revolution – a decade of mayhem from 1966 that saw thousands of temples, churches, mosques and monasteries defaced or destroyed across the country.

But now, its onion-shaped domes, elaborate motifs and Arabic script could be next in the cross hairs of a government campaign to rid the northwestern Ningxia Hui autonomous region of what it sees as a worrying trend of Islamisation and Arabisation, as the ruling Communist Party tries to “Sinicise religion”.

Throughout Ningxia, Islamic decor and Arabic signs are being taken off the streets. They only went up a decade ago, when the authorities were highlighting the Hui ethnic minority culture to lure tourists. Driving south from Yinchuan along the dusty plains of the Yellow River, the roadside is now littered with onion domes – green, gold and white – freshly removed from market buildings, hotels and parks.

Secular buildings were the first target, but the government has also banned new “Arab style” mosques, and there are plans to convert some of the existing ones to look like Chinese temples.

“The whole thing started towards the end of last year … It’s making everyone here apprehensive,” said a female staff member at the Nanguan mosque, who watched in dismay as the dome-shaped features of her home were smashed to pieces by the authorities a few months ago.

Growing unease

As the demolition and removals gather pace in Ningxia, there is growing unease among its Hui communities, who for decades have been largely left in peace to practice their faith. Descended from Arab and Central Asian Silk Road traders, there are more than 10 million Hui in China. Most of them speak Mandarin, live in peace with the majority Han population, and even look much the same as them – apart from the white caps and headscarves worn by the more traditional Hui. But as the government deepens its crackdown on Uygurs – another mostly Muslim group living in the western frontier of Xinjiang (East Turkistan) – as part of a heavy-handed fight against terrorism and Islamic extremism, the Hui in Ningxia are now also being targeted.

Calls to prayer are now banned in Yinchuan on the grounds of noise pollution – Nanguan has replaced its melodious call with a piercing alarm. Books on Islam and copies of the Koran have been taken off the shelves in souvenir shops. Some mosques have meanwhile been ordered to cancel public Arabic classes and a number of private Arabic schools have been told to shut down, either temporarily for “rectification” or for good.

China’s Hui Muslims fear education ban signals wider religious crackdown

In Tongxin, an impoverished Hui county in central Ningxia known for its elegant, Chinese-style mosque – a relic from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) that survived the Cultural Revolution – party members have been barred from going to mosques for daily prayers or making the pilgrimage to Mecca, even after they retire from office. Government workers are also banned from wearing white caps to work, local residents say.

‘Sinicising religion’

The clampdown is part of a push to “Sinicise religion” – a policy introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2015 to bring religions into line with Chinese culture and the absolute authority of the party.

“[We] should adhere to the direction of Sinicising religion in our country, and actively guide religion to adapt to a socialist society,” he said in a report to the party congress last autumn.

Of the five officially recognised religions in China, Taoism is the only indigenous one. Buddhism, though it originated in India, has also been accepted as a Chinese religion, having been, apart from Tibetan Buddhism, integrated into Han culture through the ebb and flow of dynasties.

But the party is wary of the other religions on the list – Islam, Protestantism and Catholicism – and associates them with foreign influence or ethnic separatism.

For Islam, that translates into making Muslims practice their faith in a more Chinese way – or at least in a more Chinese place.

In March, the head of the state-run China Islamic Association called for Chinese Muslims to guard against creeping Islamisation, criticising some mosques for “blindly imitating the construction style of foreign models”. “Religious rites, culture and buildings should all reflect Chinese characteristics, style and manner,” Yang Faming told the parliament’s advisory body in Beijing.

China jails Muslim man for 2 years over Islam WeChat groups

Imams and sources close to the government in Ningxia said new Arab-style mosques with large onion domes had been banned.

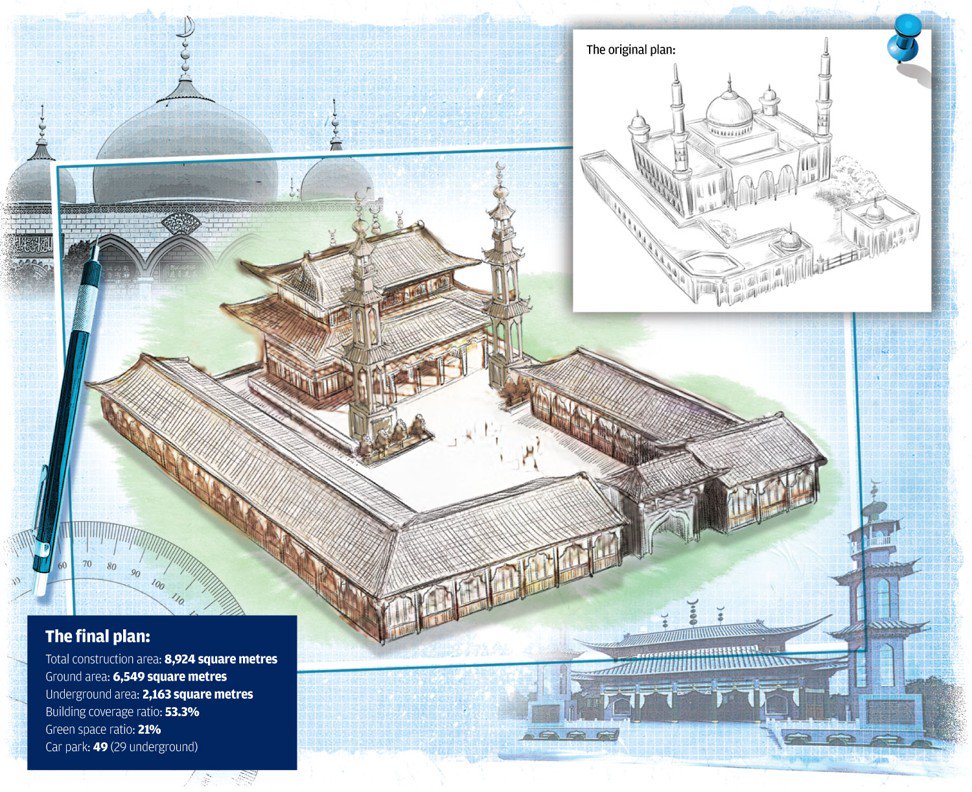

That meant a change of plan for one mosque in the west of Yinchuan. The mosque, with its traditional Chinese gateway and weathered green domes, is in the way of a road-widening project so it has to be rebuilt on an adjoining lot. Originally it was to be a Middle Eastern-style compound, with a prayer hall topped by a big white dome and flanked by two imposing minarets. People close to the mosque said the blueprint alone cost 240,000 yuan (US$37,700). But it all went down the drain when the city’s urban planning bureau rejected the design last year – no more Arab-style mosques could be approved, they were told, and it would have to be built in a traditional Chinese style.

The news came after the China Islamic Association held a seminar on mosque architecture last April, warning of the “Arabisation” trend in recent decades. “Mosques should adapt to the circumstances of our country, reflect Chinese style and blend in with Chinese culture, instead of worshipping foreign architectural styles,” it concluded in a report after the seminar.

Ransacked and destroyed

But the report left out one of the big reasons for the change in style – many of the older mosques from the Qing, Ming and earlier dynasties, which looked like traditional Chinese temples, had to be rebuilt after they were ransacked and destroyed during the Cultural Revolution set off by Mao Zedong.

“If there hadn’t been such a period of total destruction, and if all traditional Chinese-style mosques built during the Ming and Qing eras were preserved to this day, there would not have been an extensive change in style among the newly built mosques to begin with,” Zhou Chuanbin, a professor of ethnology at Lanzhou University, wrote in an academic paper.

Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai in the northwest were the hardest hit. Only one of the seven mosques in Yinchuan’s old town was left standing. In neighbouring Gansu province, there were no mosques left in Linxia, China’s “Little Mecca”, or in the capital Lanzhou, Zhou said.

China named as ‘force of instability’ in US human rights report

Compared with the traditional wooden structures, “Arab style” mosques made from reinforced concrete are a lot quicker and cheaper to build and can accommodate more people, adding to their popularity, Hui scholars said.

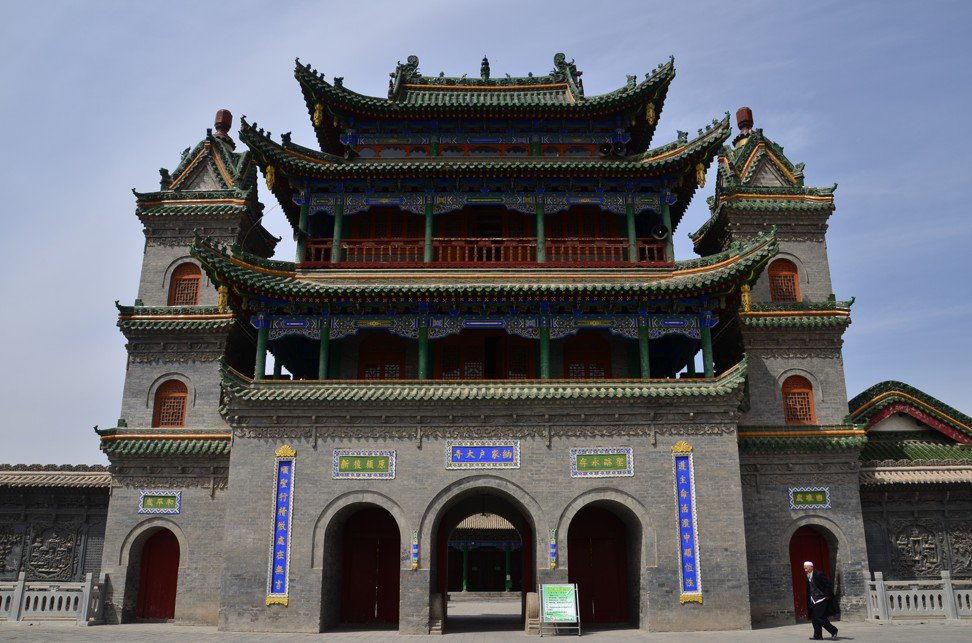

At the mosque being rebuilt in west Yinchuan, an artist’s impression shows a revised design with colourful arches, intricately carved stone balustrades and multi-tiered grey-tiled roofs curving upwards at the eaves. But it will not be wooden – that would be too costly and take too long, and the government only cares that it “looks Chinese” from the outside, according to the people close to the mosque. Construction is well under way, and the new mosque is expected to be finished by autumn.

But for some, its design is not important.

“It doesn’t really matter if the mosque is in Arab or Chinese style, as long as we’re allowed a place to pray and worship,” said a Hui man among a small crowd gathered for evening prayer.

The government’s tighter grip on religious practice is a bigger worry and has caused far more disaffection, particularly the ban on party members visiting Mecca. Known as the haj, it is one of the five pillars of Islam and all Muslims are expected to make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lives if they are physically and financially able to do so.

“I told them I would quit the party after I retire [to get around the Mecca ban], but they said that wouldn’t work,” said one party member in the crowd.

‘Wave of panic’

Not everyone wants to go back to Chinese-style mosques – for some, the onion domes and crescent moons represent the roots of Islam, a distant land where the religion began.

“It is not only that the Arab-style mosques have a long, long history – they are also a symbol of Islam for us Muslims,” said Li Jie, a 23-year-old Hui at the Beiguan mosque in Yinchuan.

That sentiment is especially shared by the Yihewani, or Ikhwan, a reformist sect of Islam that emerged in western China around the turn of the 19th century, said David Stroup, an expert on Hui Muslims at the University of Oklahoma. A response to the Chinese Sufi tradition, Ikhwan – whose followers are a minority among the Hui – is loosely seen as a more conservative and reform-oriented tradition that draws more on the Middle Eastern influence.

“There is certainly a sense among [some Chinese Muslims] that the way you ought to build a mosque should mirror the styles of mosques that are being built in Saudi Arabia – that’s the truer, more real, more accurate version,” Stroup said, citing conversations with Hui during his research in China. “In a contemporary sense, it is also a way to connect with the larger Islamic world.”

That connection is exactly what Beijing is worried about. Alarmed by jihadist terror attacks in Europe and the spread of Islamic State militants from the Middle East to other parts of the world, China is watching anxiously for any sign of extremist influence among its population of 23 million Muslims – mainly Hui and Uygurs.

In Xinjiang (East Turkistan), its answer was a sweeping crackdown on religious practice that has turned the restive region into what critics say is a “massive police state”, with thousands of Uygurs deemed prone to extremist influence detained in “re-education camps”.

“Xinjiang (East Turkistan) has very much been a model for how this is going to be carried out in other [Muslim] communities – probably not as extreme, but nonetheless I think there is going to be increased scrutiny and increased measures to control,” Stroup said.

As the authorities tighten their grip in Ningxia, Hui scholars are concerned that the region could soon be subject to the same repressive measures as Xinjiang (East Turkistan). Some fear Beijing could be using Ningxia as a testing ground for its Xinjiang (East Turkistan) policies before they are rolled out elsewhere.

“Extending the Xinjiang (East Turkistan) policies to the whole nation could be disastrous,” said a scholar in Ningxia who asked not to be named. “Such rumours have already triggered a wave of panic among the public in some places. It will damage people’s trust and support in the ruling party.”

Unity Road

Ningxia has long been portrayed as a model of “ethnic unity” by the government, a success story where the Hui and Han live a peaceful coexistence. That is why many Hui – who make up about a third of the region’s 6.3 million population – are now wondering why they have been targeted. The move has also baffled some of the Han in Ningxia, who say they have long had good relations with their Hui neighbours.

“I don’t really see the point in all of this,” said Cai Yang, a 16-year-old student sitting across the street from the Nanguan mosque.

Adjacent to the mosque is Niu Jie, a street of halal restaurants specialising in barbecued meats and noodles. There used to be a row of five small domes on its gate, but not any more.

“Every ethnicity has its own characteristics, why the need [to remove them]?” Cai said, looking across at the white archway where the domes were taken down a day before.

When the campaign to remove these features began last year, the first to go was Arabic translations on street signs, then the authorities started pulling down domes and motifs from secular buildings. After Lunar New Year in February, the Arabic logos for halal food outside restaurants and butcher shops were replaced with versions in Chinese characters and pinyin, their romanised form.

When the South China Morning Post visited Yinchuan in April, the Sino-Arab Axis – a scenic 2km park built in 2016 to celebrate the friendship between China and the Arab world – was being revamped under a new name: Unity Road.

Its two large crescent moon sculptures have been replaced with two round flat rings in the style of Chinese jade discs, while its pavilion now has a classic red roof instead of a white dome.

Grey lamp posts with Islamic motifs could be seen discarded on the ground, replaced by bright red ones with the Chinese auspicious cloud design.

Even the Hui Culture Park – a theme park on the city’s southern outskirts promoted as a window on Hui history and culture – is under “tremendous pressure” from the government to tone down its Arab elements, according to people close to the park.

Ningxia’s tourism bureau once touted the park as a cultural bridge between China and the Arab world that could “promote all aspects” of exchange and cooperation. Now it has been banned from local television because of its gold domes, the people said.

Will mosques be next?

Many Hui in Ningxia are wondering if their local mosques will be targeted in the campaign. After the Sunday noon prayer at an “Arab style” mosque in Yinchuan, one worshipper raised his concerns with the imam.

Dressed in a white turban and robes, the imam said government officials had consulted him on the feasibility of changing the style of some existing mosques.

“I told them, ‘What you do outside doesn’t really matter to us, but anything that happens to the mosque is directly tied to the feelings of Muslims … none of us will agree’,” he said.

He told the man that he was sure the policy would only apply to new mosques being built.

“There is no way the party will go after the [existing] mosques … We Muslims have always loved the country – look at our red flag,” he said, pointing at a Chinese flag fluttering from a pole between the front gate and the prayer hall, an official requirement increasingly seen in mosques in China.

But the man was unconvinced – in the past week, photos and videos of domes being taken down from two mosques had been circulating among Hui on chat groups. One of them is said to be in Wujiawan, a remote village in Tongxin, the other is in the town of Sanying, further south. There was no sign of a mosque in Wujiawan when the Post visited, but a resident of Sanying confirmed the dome from a mosque there had been removed last month.

The Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Guyuan government, which oversees Sanying, declined to be interviewed. But Guyuan Daily reported that a municipal government meeting was held last month on the progress of its “rectification campaign” against “Arabisation, Islamisation and pan-Halal” tendencies. “We should continue to reduce the number of mosques, ban unregistered religious sites, halt the progress of new mosques that are being built and put a stop to newly approved mosques,” the authorities concluded, adding that architectural styles would be “carefully classified and rectified”.

According to a source close to the Ningxia government, existing mosques could be altered “with the consent of worshippers” under the policy. But there is the question of who would pay for it, the source said. There could also be cases of local officials, under pressure to show “progress” in the campaign, forcing through changes.

Analysts said the forced removal of domes from mosques could lead to a huge backlash like the one seen in Beijing’s campaign to remove crosses from Christian churches in Zhejiang province in 2014, which drew global condemnation. That came after hundreds of Hui clashed with police in 2012 as they tried to stop their mosque from being demolished in Tongxin county after it was declared illegal. Several of the protesters were reportedly killed in the violence and dozens were injured.

With the holy fasting month of Ramadan starting on Tuesday, there is a sense of foreboding hanging over Ningxia. For now, the Hui in Yinchuan will be greeted by green domes and towering minarets when they arrive at Nanguan mosque – the first in China to open to tourists after it was rebuilt, and now a top attraction for visitors to the city.

“This was taken during Ramadan five years ago,” a woman working in the mosque’s exhibition room said, pointing to a framed photograph of a sea of white prayer caps, as hundreds of Hui spill out of the courtyard and onto the street outside. “But who knows what Ramadan will be like in the future?”