For many months, some ethnic Kazakhs who took advantage of offers of “repatriation” from Kazakhstan’s government and are now Kazakh citizens have crossed back into China, usually to the neighboring Xinjiang (East Turkistan) Uyghur Autonomous Region, as part of their business, or to visit relatives, or to take care of unfinished business, and then disappeared.

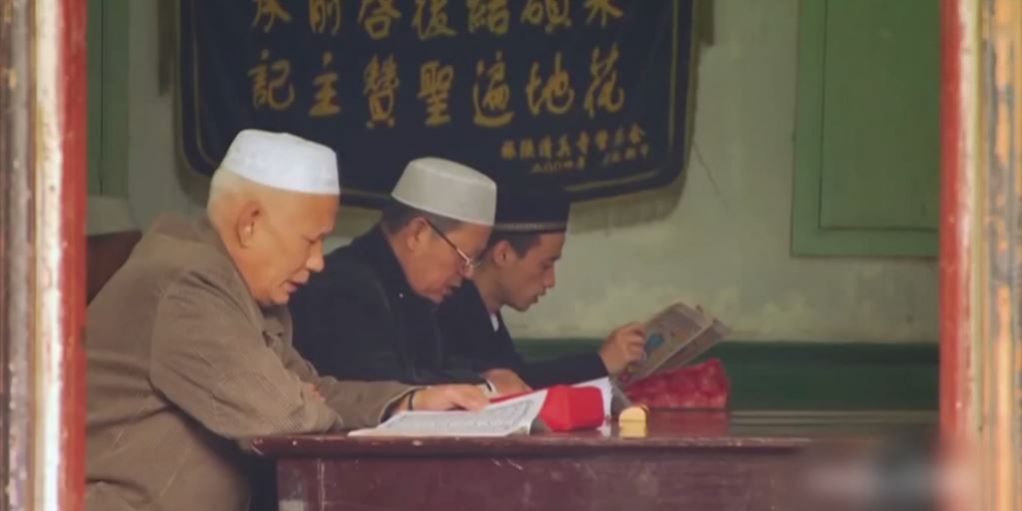

Reports suggest these Kazakh nationals were detained in China and sent to reeducation centers in Xinjiang (East Turkistan), where authorities are said to have been sending thousands of Muslims — mainly Uyghurs but later Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and even Hui, who are Chinese Muslims

Recently, some of the ethnic Kazakhs missing in China have returned to Kazakhstan. Qishloq Ovozi recounted one man’s case, and later RFE/RL’s Kazakh Service, known locally as Azattyq, reported on two other Kazakh men who were put in reeducation centers.

Kazakhstan has good reason to be cautious in its dealings with powerful neighbor China, not only because of its size and might but also because Beijing has invested billions of dollars into projects and businesses in Kazakhstan.

Radio Free Asia has reported on the incarceration of Xinjiang (East Turkistan)’s Kazakhs in reeducation centers since 2017, including Kazakh citizens.

But Kazakhstan’s government and media have largely avoided talking about its detained citizens in China. However, as some of these Kazakhs have returned to Kazakhstan, their stories have been reported by international media, making it difficult for Astana to ignore the issue.

Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement on May 28 saying that “last week in Beijing” the latest “Kazakhstan-Chinese consultations on consular matters” took place. During these consultations, the two sides discussed the “protection of the rights and interests of the citizens of the two countries, and also the mutual trips of residents of Kazakhstan and China.”

Then the most important part: “The question of the situation of ethnic Kazakhs, who have resettled from China to Kazakhstan and have become citizens of the Republic of Kazakhstan, was raised by the Kazakh side. An urgent request was expressed about an objective and fair review of affairs and the release of those ethnic Kazakhs detained in China who have dual citizenship.”

The Kazakh delegation wasn’t exactly holding the Chinese feet to the fire with that statement, but diplomacy is often a delicate art, especially when you represent a country of 18 million people in a conversation with representatives of a country with 1.4 billion people.

Kazakh Foreign Minister Kairat Abdrakhmanov said on May 29 that he had information about some 170 ethnic Kazakhs “experiencing difficulties” in China. But he said that of those, only 12 were Kazakhs who had become citizens of Kazakhstan and nine of them were already back in Kazakhstan. He said the citizens of Kazakhstan who were detained “could not properly complete the documentation for revoking their Chinese citizenship and were detained.”

The Kazakhs who got out of China confirmed they were originally taken into custody because Chinese authorities said they had not completed all the necessary procedures to cancel their Chinese citizenship and were therefore still considered citizens of China. However, as noted in previous reports, they were said to have then been put in centers where long daily lessons were given on the Chinese government’s policies and devotion to the homeland.

Poking The Dragon

All this puts Kazakhstan’s government in a difficult situation. The “oralman” program that invited ethnic Kazakhs to become citizens has added 1 million people to Kazakhstan’s population, and, as important, these are all ethnic Kazakhs, something that has helped tilt the demographic balance in Kazakhstan in favor of the titular nationality. Kazakh officials might never have guessed in the early 1990s when they initiated the program that it could ever become a sore point in relations with its giant neighbor.

Furthermore, anti-Chinese sentiment appears to be growing in Kazakhstan. It started with an increasing number of Chinese workers arriving to participate in projects that China was helping to finance, but it exploded in spring 2016 when rumors spread that a new land law would allow Chinese citizens to buy land in Kazakhstan. Social tensions over hard economic times had been festering, and these rumors of alleged Chinese land ownership lit a fuse that set off the biggest protests Kazakhstan had seen since the late 1990s. The government calmed the situation by calling off the land-privatization plans.

But it did not alleviate anti-Chinese sentiment in Kazakhstan, and now Astana may well be approaching a pivotal moment in its relations with China. Attention to the detentions of ethnic Kazakhs in China is growing. It was also recently revealed that Kazakhstan’s government had approved a three-day visa-free regime for Chinese nationals to visit Kazakhstan. The move elicited strong objections among Kazakhs on social media.

On May 31, the eve of International Children’s Day, a group of some 20 Kazakh children whose parents are being kept in reeducation camps in Xinjiang (East Turkistan) were reportedly brought by their relatives to a press conference in Almaty, where they made a public appeal to Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbaev to get their fathers out of detention in China.

Attending the press conference was Omirkhan Altyn, an ethnic Kazakh living in Germany. Altyn was among the first people to publicly raise the issue of the treatment of ethnic Kazakhs in China when he attended a world Kuriltai of the Kazakh diaspora in Astana in April 2017 and called on Nazarbaev to do something about the situation. At the May 31 press conference, Altyn said, “These children cannot celebrate as other children are [on International Children’s Day]. Chinese authorities have put the parents of these children in detention, violating the rights of these children.”

Treading A Fine Line

That was not the only press conference on this topic recently. On May 25, Uali Silam, an ethnic Kazakh from China who has been a citizen of Kazakhstan since 2017, appeared at a press conference in Almaty with his two children, appealing to authorities in Kazakhstan not to send his wife back to China.

Salim came to Kazakhstan in 2016, but his wife, Sayrangul Sauytbek, still hasn’t completed all the steps necessary to emigrate. Now, she might never finish the process.

Sayrangul Sauytbek crossed into Kazakhstan illegally in April. Chinese authorities discovered this and contacted Kazakhstan requesting that Sauytbek be detained and returned to China. Kazakh authorities did detain her on April 21, according to Silam, but she has not been extradited.

Kazakhstan has, over the course of around two decades, extradited several ethnic Uyghurs who were Chinese nationals to China, but Kazakhstan never appears to have deported an ethnic Kazakh to China.

The voices of “repatriate” Kazakhs in Kazakhstan are receiving a lot more attention in Kazakhstan lately. The responses from Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry and foreign minister show the government feels the need to prove it is addressing the issue.

But Kazakh authorities are walking a tightrope, seemingly trying to maintain good relations with China while preventing this issue from sparking unrest among Kazakhstan’s population.

In Astana’s favor, Kazakhstan sells oil, natural gas, and uranium to China, and Kazakhstan is a key country in Beijing’s One Belt One Road global trade-network project, since railway links westward from China and to the Persian Gulf pass through Kazakhstan. It’s seemingly in China’s interests to somehow resolve this situation, at least with those ethnic Kazakhs who now have citizenship in Kazakhstan.