By Wang Lixiong, published March 3, 2014

(On the evening of March 1, 2014, several knife-wielding men and at least one woman killed 33 and injured more than 140 in the train station in the southwestern city of Kunming. The Chinese authorities blame Uyghur separatists for the terrorist attack. — Editor)

People asked how I look at the Kunming incident. I don’t feel I have much more to say. The issue lies not in the incident itself but beyond it, and it has been long in the making. I have said everything in my bookMy West China; Your East Turkestan (《我的西域; 你的东土》) published in 2007. I offer the following excerpts from the book to serve as my answer:

What is “East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))?” Its most straightforward meaning is “new territory.” But for the Uyghurs, how could the land possibly be their “new territory” when it has been their home and their ancestors’ home for generations. It is only a new territory for the occupiers.

The Uyghurs don’t like to hear the name “East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))” because it is itself a proclamation of an empire’s expansion, the bragging of the colonists, and a testimony of the indigenous people’s humiliation and misfortune.

Even for China, the name “New Territory” is awkward. Everywhere and on every occasion, China claims that East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) has belonged to China ever since ancient times, but why is it called the “new territory?” The government-employed scholars racked their brain, insisting that “new territory” is the “new” in the phrase “the new return of old territories” by Zuo Zongtang’s (左宗棠, best known as General Tsao who led the campaign to reclaim East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) in 1875-1876). This is far-fetched, because in that case, shouldn’t it be called the “old territory”?

I will never forget a scene once described by a foreign journalist in which, every evening, a seven-year-old Uyghur boy unhoisted the Chinese flag, which the Chinese authorities required them to fly during the day, and trampled it underfoot. What hatred would make a child do that? Indeed, from children, one can measure most accurately the level of ethnic tension. If even children are taking part in it, then it is a united and unanimous hostility.

That’s why, in Palestinian scenes of violence, we always see children in the midst. I use the term “Palestinization” to describe the full mobilization of a people and the full extent of its hatred. To me, East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) is Palestinizing. It has not boiled to the surface as much, but it has been fermenting in the heart of the indigenous peoples.

The indigenous peoples regarded Sheng Shicai (盛世才) , the Han (Chinese) war lord who ruled East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) during the 1930s and 1940s, as an executioner, and they call Wang Lequan (王乐泉), the CCP secretary who carried out heavy-handed policies in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), Wang Shicai. But when, in Urumqi, the Han taxi driver saw I was holding a copy of Sheng Shicai, the Lord of the Outer Frontiers, a book I had just bought from a bookstore, he immediately enthused about Sheng. “The policies at his time were truly good,” he exalted.

CCP’s policies in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) today have been escalating the ethnic tension. Continuing on that path, it will not take long to reach the point of no return where all opportunities for healthy interaction will be lost, and a vicious cycle pushes the two sides farther and farther apart. Once reaching that point of no return, East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) will likely become the next Middle East or Chechnya.

Once, I asked a Uyghur youth whether he wanted to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. He said he wanted badly, but he cannot go now because the Koran teaches him that, when your homeland is still under occupation, you cannot make pilgrimages to Mecca. He stopped short there, but the idea was clear. To fulfill his wish, he will fight to drive the Hans out of his homeland.

However, I am more shocked by Han intellectuals, including some elites at the top. On any normal day, they appear to be open-minded, reasonable, and supportive of reform, but as soon as we touches the topic of East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), the word “kill” streams out of their mouths with such facility. If genocide can keep East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) under China’s sovereignty, I think it is possible that they will be able to stay composed and quiet if millions of Uyghurs are killed.

If the oppression is political oppression, once the political system changes, the oppression will be lifted, and I suppose all ethnicities should still be able to live and work together to build a new society. But if the minorities believe that the oppression comes from the Han people, then political change will not solve the problem fundamentally. The only option will be independence.

This is a factor working against China’s political transition, because, instead of helping keep the minorities in China, political change will weaken the Chinese control, and the indigenous peoples will seek independence.

As an observer of the CCP’s power operation, I often see in my mind’s eye a scene you would see in Chinese acrobatics: one chair stacks on another, another and another, with the performer turning upside down one moment and swiveling around the next on top of them. Today, the CCP’s acrobatic skills have also reached such virtuoso levels, stacking chairs to an incredible height. However, the balance will not last forever, and the chairs cannot be stacked to an indefinite height. There will be a moment when all chairs will tumble down. The taller the chairs have been stacked, the harder they will collapse.

Over the CCP’s rule of more than half a century, the humanistic tradition has been cut off, education of humanities has been marginalized and has become insignificant. Even the new generation of bureaucrats, who are considered to have received a good education, are mere technocrats who have knowledge but no soul and who worship power and look down on the poor and the weak. They rely on nothing else but the power system and the art of power struggle; they are good at nothing but using such administrative power as a means of suppression. They churn out phrases like “step up,” “strike hard,” “punish severely” every time they talk. It seems to work for the moment, but it is drinking poison to quench the thirst.

In the absence of the humanistic spirit, the power group has no capacity to face deeper areas of culture, history, faith, and philosophy. Their solutions tend to be wretched and simplistic, calming down disruptive incidents like a fire engine darting out to distinguish a fire. But the ethnic problem is precisely a humanistic issue and the correct way of solving it is only attainable through a humanistic approach. Looking ahead, it is hard to expect the CCP to make any breakthroughs, because the revival of humanistic values cannot be done in a snap.

Throughout its history, East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) was twice “East Turkestan” (once in 1933 and another time in 1944). But China in the last century also saw various separatist rules, including the Communist Party’s “Soviet Republic,” resulting in China’s continuous division. In fact, the escalation of the East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) problem almost coincided with Beijing’s “anti-separatism struggle” in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)). Therefore, we have reason to believe that, the East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) issue to a large extent is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

[In 2000, the CCP issued Document No. 7 with regard to the East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) issue. This is how it described what is at issue: “The principal danger to East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))’s stability is the separatist force and illegal religious activities.” The syntax resembles Mao Zedong’s edict about East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) [in 1962 when China and USSR turned from “brothers” to enemies]: “the principal danger in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) comes from the Soviet Union’s modern revisionism.” The difference is the focus has turned from international relations to ethnic relations. And this document has since become the CCP’s guidelines and policy foundation for carrying out hardline approaches in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)).

The crackdown has been strengthened, but terrorist activities have picked up. Why? Is there a cause-and-effect correlation between the two? It is possible that some terrorist groups and activities are the creations of the CCP’s “prophecies.” The CCP’s own creator Mao Zedong said long ago that “there is no such thing as hate without a reason,” but Beijing has not pause to consider the most important question: What are the reasons and causes of ethnic hatred in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))?

When Document No. 7 insists that “the principal danger to East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))’s stability is the separatist force and illegal religious activities,” it separates the Hans and the indigenous peoples living in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) into two groups, pitting them against each other, because both the “separatist force” and the “illegal religious activities” are aiming at the indigenous peoples.

Naturally, Beijing has been relying on the Hans living in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) to carry out its administration, and the indigenous peoples on the other hand have become groups on whom watchful eyes must be kept. Consequently, all the “prophecies” are being self-fulfilled: The Hans are vigilant toward the indigenous peoples, and the indigenous peoples eventually will be driven to the opposite side. A small number of terrorists are not a big problem; the biggest danger is when the indigenous peoples in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) as a whole turn against Beijing.

With the idea of stabilizing East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) through economic development, the basic mistake is that the essence of the ethnic issue is not economic but political. To begin with, it is upside down to solve a political problem with economical solutions, and how do you expect to solve the ethnic problem when high-strung political suppression continues to ratchet up?

Beijing likes to flaunt how much money it has given East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), but the indigenous peoples are asking: How much oil have you siphoned away from East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))? The Number One project in China’s “Grand Development of the West” is “the transportation of natural gas from the west to the east.” The East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) residents have legitimate reasons to question whether the development of the west is in fact a plunder of the west. As long as the hostility exists and different ethnic groups distrust each other, all economic activities can be labeled as colonialism.

Hans are 40% of the East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) population but they have controlled most of the power and the economic and intellectual resources in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)). They are positioned to grab more benefit than the indigenous peoples in any given new wealth distribution or new opportunities. East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))’s economy depends on the interior of China. The use of Mandarin alone puts the indigenous peoples at a disadvantage. Today, if you are looking for a job in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) but don’t speak Mandarin, you will be dismissed right away. High-level positions are mostly held by the Hans.

Unemployment in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) is severe. Young people often can’t find a job. Han residents can go to the interior to work, but the indigenous people can only stay home. When I travelled in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), I saw ethnic youth loitering together chatting or carousing. Scenes like that always troubled me because, what would the future hold if so many young people are idling, having no place to make better use of their energy, while hatred keeps growing?

A Uyghur friend told me, “Look, 99% of diners in these little restaurants are Uyghurs and 99% of them are paying from their own pockets. But 99% of the customers in big restaurants are Hans, and 99% of them are paying bills with public money!” The discontent of ethnic minorities first and foremost came from such visual and straightforward contrasts. Indeed, in expensive venues in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), there were hardly any ethnic people. There, it felt just like China’s interior with Hans all around speaking Chinese.

As with any changing circumstances, there is a tipping point. Before reaching that point, there might be room for improvement. But once past the tipping point, the situation will be similar to the kind of ethnic war between the Palestinians and the Israelis that has no solution and no end in sight. I cannot estimate how far we are from that tipping point, but following the path the current regime is walking on, we are fast approaching it.

The CCP seems to believe that, with the grip on power, they can do anything they want without having to care about the feelings of the indigenous peoples. A typical example is that they sprinkled Wang Zhen (王震)’s ashes in the Heavenly Mountains. (Wang Zhen was one of the eight “lords” of the CCP and the first party secretary in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)).) For the indigenous peoples, all water comes from the sacred Heavenly Mountains (天山). The Muslims have particular concepts of being clean, not just tangibly but also intangibly. Ashes are not clean; on top of that, Wang Zhen was a heretic and a murderer, and to spread his ashes was to foul all of the water for Muslims.

Having ruled East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) for decades, the Chinese government’s impertinence was such that, to satisfy Wang Zhen’s wish, the will of more than 10 million Muslims living in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) must be cast aside and the event must be broadcast loudly. Indeed, East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) Muslims couldn’t do anything about it and still had to drink water. But you can imagine every time a East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) Muslim drinks water, how he or she would be irritated by the idea of uncleanness, and how they would think that, if East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) is independent, such a thing would never have happened.

The mosques are not allowed to run schools to teach the Koran. But how can you prohibit a religion from preaching its beliefs? When the students cannot study Koran in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), they will have to go to Pakistan, Afghanistan … in the end some of them will be turned into Talibans and get Jihad indoctrination and terrorist training. Finally they will return to East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) to engage in terrorism and fight for the freedom of spreading the Islam.

When people petition, protest, even provoke disturbances, it means they still harbor hopes for solutions. When they cease to say or do anything, it is not stability; it is despair. Deng Xiaping was right when he said, “the most terrifying thing is when the people are stone quiet.” Unfortunately none of his successors really understood him. Today the rulers are rather complacent about the general silence. Any expression of resistance by the Uyghurs will be met with head-on blows.

Eliminating conflicts “at the germinating stage” isn’t a good way to deal with conflicts, because the nature of the conflict doesn’t manifest itself in that early stage, while many positive factors can also be eliminated. That’s not really eliminating the friction, but suppresses it or rubs it in deeper. It will pile up and there will be a day when it will be triggered unexpectedly: out of silence thunders crashes down.

If the percentage of Hans in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) are small, they would retreat to the interior as soon as there are signs of unrest. Conversely, if the Han immigrants outnumber the indigenous peoples with even more advantages than numbers, then the indigenous peoples would shun rashness. But now is a time when conflict is mostly likely because the Hans and the indigenous peoples are closely equally numbered.

Han is the second largest ethnic group in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)). A considerable portion of them have long put down roots in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), and some have lived in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) for generations already. They don’t have anything in the interior, and they will defend East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) as they would their homeland. This means that, when Hans in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) are faced with ethnic conflict, they are unlikely to exercise restraint. Instead, they would use the weapons, the fortunes, the technology and the leadership positions they have at their command to fight the indigenous peoples, with the help of the great China behind them.

When the Uyghurs begin a Jihad against the Chinese rule, will other Muslims join their cause, such as the Caucasians, the Afghans, and rich Arabs? The separatists know very well that they can’t confront China by themselves, so they have always put their cause in the larger picture of the world. I have heard them talking about East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan))’s geopolitics, the world of Islam, and the international community, and I was surprised by their wide visions.

When the time comes, East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) will simultaneously have organized unrest and random disruptions, prepared armed actions and improvised terror attacks. Overseas Uyghurs will get involved, and international Muslims will also intervene. In a convergence like that, the conflict will inevitably escalate. It will not be easy for the Hans to put East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) under control, but on the other hand, once hatred is being mobilized, it will see no end, and the killing will be imaginably frantic and ruthless.

In East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)), an Uzbek professor told me that China is bound to slip into chaos in the future, and the day China democratizes will be the day when East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) will be in a blood bath. Every time he thinks about it, he said, he is scared, and he must send his children abroad, away from East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)).

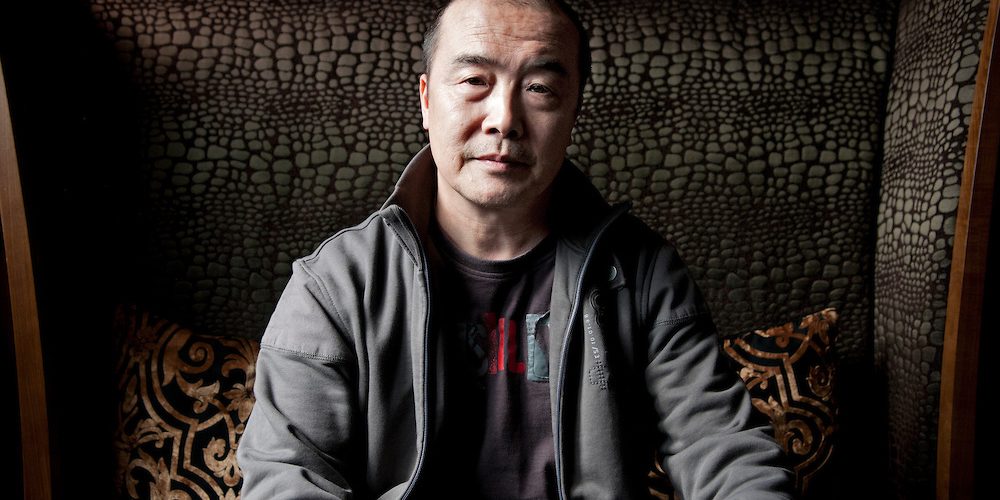

Wang Lixiong (王力雄) is a Beijing-based Chinese writer best known for his political prophecy fiction, Yellow Peril, and for his writings on Tibet and China’s western region of East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)). Wang is regarded as one of the most outspoken dissidents, democracy advocates in China. Between 1980 and 2007 when this book was finished, he made nine trips to East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) and his travels brought him to every part of the region. While traveling in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) in 1999, he was briefly detained by the Chinese secret police for suspicion of collecting classified information. But his prison time in unexpected ways helped the writing of this book. Wikipedia (in English) has a list of Mr. Wang Lixiong’s works.

Wang Lixiong (王力雄) is a Beijing-based Chinese writer best known for his political prophecy fiction, Yellow Peril, and for his writings on Tibet and China’s western region of East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)). Wang is regarded as one of the most outspoken dissidents, democracy advocates in China. Between 1980 and 2007 when this book was finished, he made nine trips to East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) and his travels brought him to every part of the region. While traveling in East Turkistan (Xinjiang (East Turkistan)) in 1999, he was briefly detained by the Chinese secret police for suspicion of collecting classified information. But his prison time in unexpected ways helped the writing of this book. Wikipedia (in English) has a list of Mr. Wang Lixiong’s works.

Read the complete book My West China; Your East Turkestan here (in Chinese).